Laurie's Blogs.

Feb 2021

Why Animal Physiotherapists do not treat arthritis (but don’t tell anyone).

By Ansi van der Walt, MSc Physiotherapy

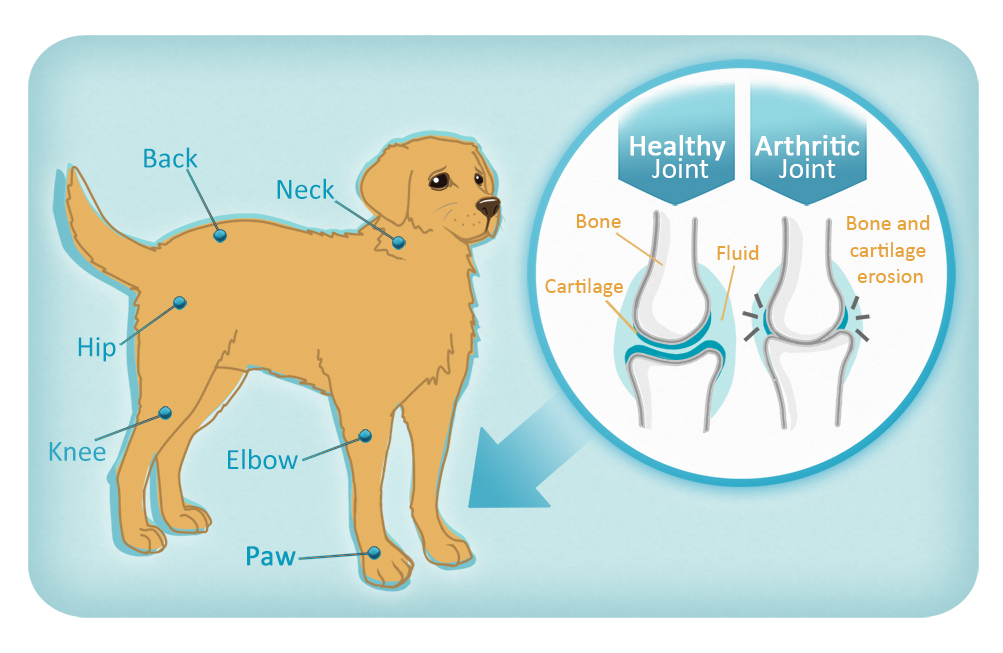

What is arthritis? Good question. Opinions as to what diagnostic criteria constitute the pathology broadly referred to as osteoarthritis (OA) differs in literature. There are three broad definitions of osteoarthritis. These are radiographic OA, symptomatic OA and self-reported OA. For the purposes of this article, we will focus on radiographic and symptomatic OA only, as animals are unable to self-report symptoms.

Radiographic OA by definition considers only pathophysiological joint signs present on radiographic images, which can be graded (scored). However, many people (and animals) have radiographic signs of joint degeneration without ever experiencing related symptoms or disability, so is this really arthritis? It has been shown that over 40% of adults over the age of 40 will have MRI features of osteoarthritis in at least one knee, without ever having had any symptoms (2). Symptomatic OA considers both radiographic evidence of joint pathology, as well as symptoms such as pain, stiffness and loss of function in reaching a diagnosis (1). In a review of patients diagnosed with osteoarthritis in UK primary care, 75% were treated by analgesics (3), so we can safely assume that the majority of animals presenting for veterinary care that are diagnosed with osteoarthritis, were observed to be in some degree of discomfort, and therefore fall into the symptomatic OA group.

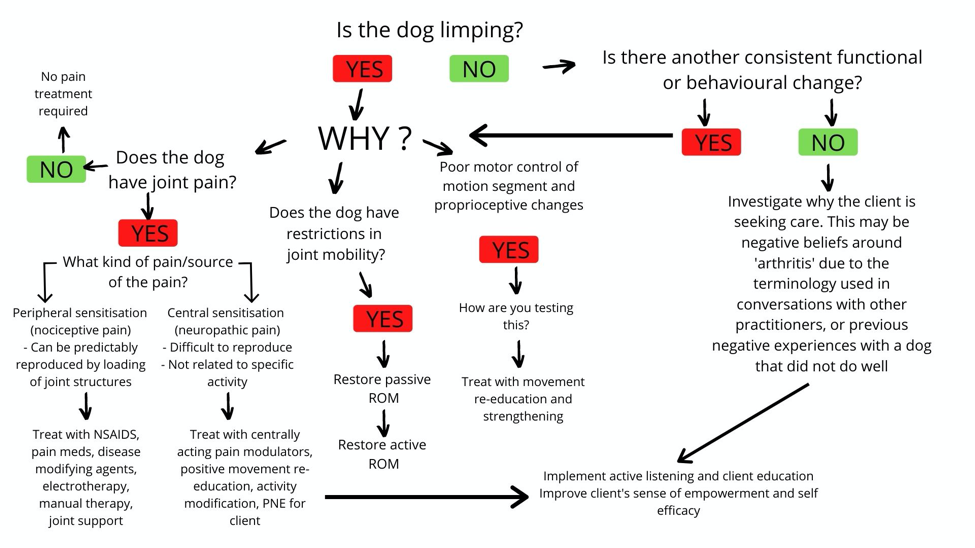

In short, owners do not seek help for their pets because they have ‘arthritis’. Owners take their dogs or cats or horses to the vet because they have developed a dysfunction – they are limping (most commonly), or demonstrating some change in behaviour. It is not simply the presence of degenerative joint changes that causes the discomfort. We know this, because many patients with degenerative changes seen on diagnostic imaging have no joint related symptoms. We also know that some patients with mild radiographic changes experience severe symptoms (4). It is good that there is no direct correlation between the radiographic features of osteoarthritis and the symptoms experienced by a patient, as there is no way of reversing, or “treating” those aspects of the disease (osteophytes, cartilage disruption, joint space narrowing), short of replacing the or removing the diseased joint.

What we can, and do treat, are the dysfunctions that have arisen in association with the changes occurring in the joint(s). Our goals with treatment are to modify the progression of the joint pathology, and optimise each individual’s function within his/her individual contexts.

Factors that have been shown to be predictors of functional decline in osteoarthritis patients are (5):

- Joint pain (dysfunction in immunomodulation and central pain regulation)

- Joint laxity (structural dysfunction as well as dysfunction of motor control)

- Lack of aerobic exercise (general deconditioning)

- Lack of self-efficacy (Dysfunctional relationship between the animal, owner pain beliefs and its environment).

Because there is such variability in etiology, presentation and progression of OA in different dogs, and because every dog’s daily challenges are different, this is a perfect example of treating the patient, NOT the diagnosis.

The key to long term success in treating animal OA is to address the functional change that worries the owner enough to seek care for the patient. This may mean counselling the client on short or long term activity modification in addition to addressing the assessed deficits that the patient presents with. Because OA patients are often presented as chronic pain patients, or could easily transition to a chronic pain state, the physiotherapist must become very proficient at applying pain neuroscience education and support in the context of pet ownership.

References:

1.D. Pereira; B. Peleteiro; J. Araújo; J. Branco; R.A. Santos; E. Ramos (2011). The effect of osteoarthritis definition on prevalence and incidence estimates: a systematic review. , 19(11), 1270–1285. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2011.08.009

2.Culvenor AG, Øiestad BE, Hart HF, et alPrevalence of knee osteoarthritis features on magnetic resonance imaging in asymptomatic uninjured adults: a systematic review and meta-analysisBritish Journal of Sports Medicine 2019;53:1268-1278.

3.Anderson, K.L., O’Neill, D.G., Brodbelt, D.C. et al. Prevalence, duration and risk factors for appendicular osteoarthritis in a UK dog population under primary veterinary care. Sci Rep 8, 5641 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23940-z

4.Jones, L.D., Bottomley, N., Harris, K. et al. The clinical symptom profile of early radiographic knee arthritis: a pain and function comparison with advanced disease. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 24, 161–168 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-014-3356-z

Issa, S.N., Sharma, L. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis: An update. Curr Rheumatol Rep 8, 7–15 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ansi van der Walt (MSc Physiotherapy) is a Johannesburg based Veterinary Physiotherapist who has been working in the field of animal physiotherapy since she qualified in 2001. A passionate advocate for evidence-based practice in animal therapy, Ansi is also deeply involved in the training and regulation of animal physiotherapists in South Africa, serving on various professional committees. Ansi’s special interest lies in exercise-based rehabilitation interventions and improving client self-efficacy in chronic pain conditions.

You can find her at: https://www.fitness4pets.com/