Laurie's Blogs.

Apr 2016

When and why to treat an asymptomatic dysfunction?

Confession! I have an assistant (Rebecca) that helps me comb through blogs and research articles, so that I can be up to date and can generate ideas on topics to present, blogs to write, and info to pass along to you! This week, my blog update report contained a number of interesting blogs, and the one that caught my attention the most was a Podcast from www.mikereinhold.com, and it tackled the questions of : Should we treat people with asymptomatic movement dysfunctions? Great question, eh?

Okay, so here’s what the panel of physical therapists had to say:

1. What does the patient want to do? (i.e. are they a pitcher, or a weight lifter and they have a thoracic spine movement restriction?)

If that’s the case, then YES! Absolutely yes! Often when there is an injury and pain, and we assess these patients, we will commonly find a dysfunction elsewhere. So to fully recover from the injury and prevent it’s reoccurrence, the ‘asymptomatic’ dysfunction needs to be addressed.

Here’s another example. I saw one of my dog owner clients a month or so ago. (I really try to not treat humans...) She was starting back to running, but was having pinpoint pain at her ischial tuberosity. She figured she needed to stretch her hamstrings. However, on examination, her ischial tuberosity wasn’t really painful to the touch and her hamstrings were fabulously flexible, but her muscle firing patterns were all ‘out of whack’. Her gluteals weren’t helping at all! (Then what? Then her hamstrings have to do the work. And most likely what she was experiencing was hamstring fatigue.) So her ‘asymptomatic dysfunction’ was weak gluteals and poor motor control and timing with them!

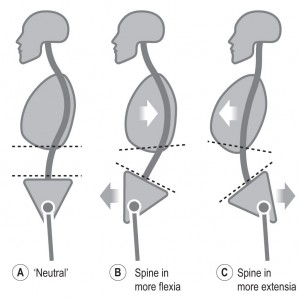

2. Optimizing motion and or helping the patient to move better.

Depending on the ‘goal’ of the patient (i.e. What do they want to do?), is there rationale for helping them to move better? We know that especially in athletes, better movement and optimized motion (and motor control) can help to prevent injuries. So, does this not make sense to evaluate movement, motion, and motor control in people that want to avoid injury and whose ‘job’ demands full function? Can I get a “Yah sister!” on that one!?

Now how does this apply to our canine patients?

- Is your patient an athlete? Do he/she compete in flyball, agility, obedience, rally-o, herding, field trials, hunting trials, scent hurdle, earth dog, freestyle, frisbee, etc? If yes, then they need a routine maintenance assessment & treatment to prevent issues.

- Is your patient a show dog? And as such, does the owner or handler care about proper movement in the show ring and/or proper conditioning of the dog? If yes, then they should be routinely checked and treated if required.

- Has your patient recovered from a previous injury (i.e. ACL surgery, elbow surgery, spinal joint dysfunction, spinal surgery, etc)? If yes, then offering to do a check up on a quarterly or tri-annually basis would be in order.

- Have you discovered your patient to have a chronic issue (i.e. osteoarthritis, hip dysplasia, elbow dysplasia, an off-again-on-again soft tissue lesion)? If yes, then some form of treatment could be in order from a pain management, joint health, or soft tissue injury prevention standpoint. The time between maintenance appointments will need to be ‘guessed at’ at first and then modified there-after (sort of like determining how frequently to administer Cartrophen or Adequan injections). Was the dog really sore at the 6-week mark? They try a follow-up at the 4-week mark.

And lastly, this points out as well, how important it is to look at the whole body, not just the injured / painful area! Because a movement dysfunction could lead to something else or be the root of the problem at hand.

Okay folks, so go out there and make a big impact on your patients today (and all week long)!

Cheers! Laurie