Laurie's Blogs.

Mar 2023

Stifle pain but no cruciate disease… now what? (part 1)

GUEST BLOG

I had two patients present this last fall that shared a lot of similarities. Both were young, high drive dogs. Both had incurred an injury during the course of routine play behaviour, and both had been diagnosed with cruciate disease prior to arriving on our doorstep. There was definitely stifle region pain in each case, but in the end neither case proved to have cruciate disease. For me, they were a good reminder to always keep an eye out for the “zebras”.

Case #1

A 10 month old female border collie agility prospect presented with an acute onset left hindlimb lameness after running in a field. No specific trauma was observed. Video footage provided by the owner showed a poorly weight bearing (4/5) LHL lameness, with a tendency to keep the stifle extended when either sitting or lying down.

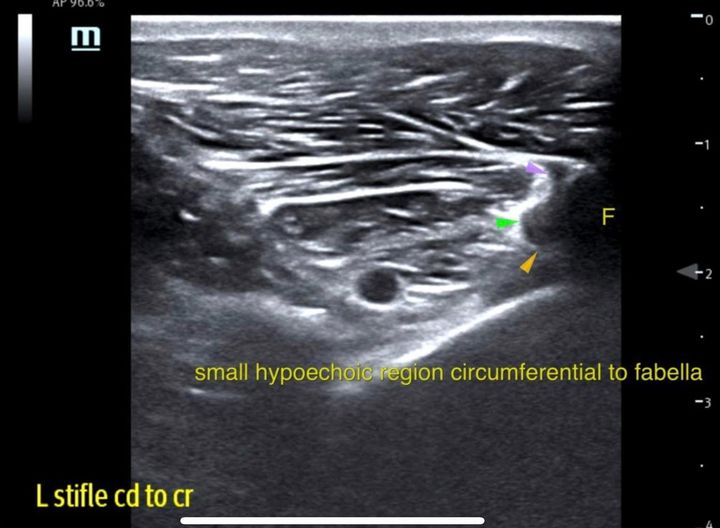

On physical examination, there was repeatably pain on stifle extension, but no palpable effusion or instability. However, there was also focal repeatable pain when palpating the caudal medial aspect of the lateral fabella. Although the history and subjective gait assessment were highly suggestive of a cruciate disease, the physical examination findings suggested we might be looking at something different. The patient was sedated and orthogonal radiographs of the lumbar spine, hips, and stifles were taken. No abnormalities were seen, including no evidence in intra-articular stifle inflammation.

Armed with this additional evidence that the patient did not have cruciate disease, we proceeded to ultrasound. Longitudinal and transverse images of the caudal stifle collected and uploaded to a radiologist. Consistent with the physical examination findings, the ultrasound report demonstrated a partial avulsion of the lateral head of the gastrocnemius (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Gastroc Avulsion

We had several treatment options before us. In general, my preferred treatment for grade II soft tissue injuries resulting in macroscopic defects (especially in athletic dogs) is to leap to regenerative medicine – combining some sort of stem cell product with PRP and injecting it into the lesion under ultrasound guidance. Research on this treatment for muscle tears is scant in dogs, but there is one paper that showed good results when performing this procedure to address hamstring myopathy (acute myopathy, not fibrotic myopathy) in GSDs. However, because of the patient’s young age, and the fact that the defect was at the muscle’s origin instead of being located mid-belly (thus reducing my fear that scar tissue formation would interfere with the final outcome), it was decided that a less invasive option would provide the same results.

Extracorporeal Shockwave (ESWT) would be my next preferred modality, but the owner had travelled a great distance for this appointment, so repeatedly returning on a weekly or biweekly basis was not an option. Unfortunately, there was no access to an ESWT machine closer to home. Also, this patient was prone to anxiety, so there was some question about how well she would tolerate shockwave without concurrent IV sedation.

Thus, we decided to proceed with biweekly lasering at a rehab facility closer to home for 3 weeks, followed by weekly lasering for 5 weeks, therapeutic exercises focused on maintaining flexibility for that 8-week period, and recreational exercise confined to leash walks on easy terrain. We also intended to modify the exercise schedule over time, depending on the amount of improvement seen in the patient’s comfort. The ability to comfortably maintain a proper square sit position, and comfort following exercise, were used as the main metrics for measuring improvement.

8 weeks later, the patient’s comfort had improved, but the lameness was not fully resolved, and there was a mild setback in comfort just after the 7-week mark. Consequently, we decided to repeat a diagnostic ultrasound of the lesion to confirm we were making appropriate progress (Figure 2). The radiologist’s comments were that, “prolonged recovery is something that is very common, especially with gastrocnemius musculotendinopathy so that the ultrasonographic and clinical changes appear to be within the expected limits.” I confirmed that this impression was based on the radiologist’s subjective experience, and that no such data has been published. In the end, this comment was prophetic.

Figure 2. Gastroc Avulsion after 8 weeks of laser treatment

Unfortunately, the patient’s anxiety and reactivity issues had worsened, to the point where it interfered with our ability to assess for pain during a physical examination, or for anyone’s ability to apply laser therapy without triggering a negative emotional response. Thus, we decided to discontinue laser treatment and focus solely on exercise modification and therapeutic exercise, while the owner worked separately on the patient’s reactivity issues.

As of the time of this writing, 6 months has passed since the time of the original diagnosis. There have been ups and downs in terms of patient progression but the trajectory of the graph has been positive. She is going for 45 minute walks in the woods, and working with an online conditioning coach for therapeutic exercises. The recent deep snow has caused some brief stiffness following hikes, so the owner is focusing on increasing the strengthening exercises until the weather improves. Recent examination indicates the soreness is of lumbopelvic origin, rather than from the site of the original lesion; fabellar palpation revealed no pain, and no defensive reactivity. The owner is going to initiate off leash time on easy terrain, and some agility grid jumps at a lower height.

Although I’m happy this case is headed toward a positive outcome, the process is taking longer than I would have expected. Were it not for the benefit of the original ultrasound image, coupled with the follow up report showing significant improvement, I would have definitely been second guessing my diagnosis… wondering if it was a partial cruciate tear after all, or if it was some other zebra diagnosis that might not carry the same long term prognosis. In cases like this, I am a strong proponent of the use of imaging to gain a precise diagnosis, and not monkeying around with crossed fingers or vague answers about what is going on when the patient experiences a setback.

Having said that, I often find myself discouraging owners from obtaining images even though they are requesting them. Most commonly this occurs with non-specific back pain patients. Research has shown that vertebral radiographic changes correlate poorly with patient function, and with IVDD diagnosis. Therefore, when first presented with a back pain dog, I don’t routinely request radiographs because it is unlikely to affect my treatment plan. However, if I treat the dog, and the back pain doesn’t resolve as expected, I will likely request radiographs at that point to see if we can learn why, but that situation is the exception, not the norm.

Similarly, owners will ask about repeat imaging known arthritic joints. I discourage that as well for the same reasons – radiographic appearance is a poor predictor of patient comfort, and even if we document progression of the OA, that information will not affect the treatment plan. For me, it is patient comfort that drives the treatment plan.

And learn more about Dr. David Lane by visiting his website at: https://www.pointseastwest.com/