Laurie's Blogs.

Feb 2023

Part 2 - Iliopsoas? Nope! Immune Mediated Polyarthritis!

GUEST BLOG

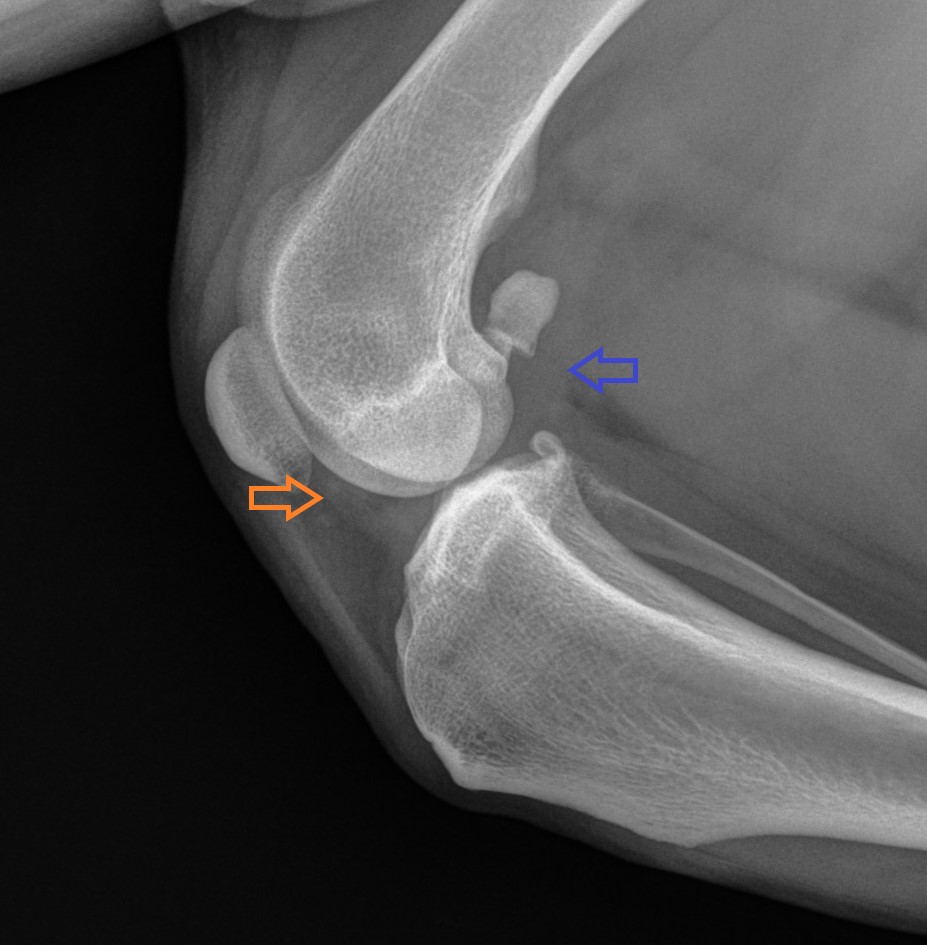

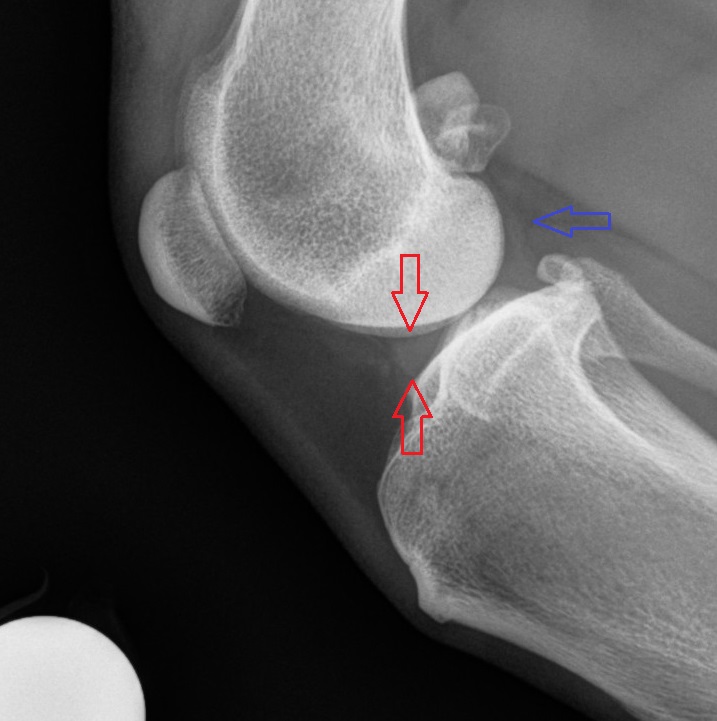

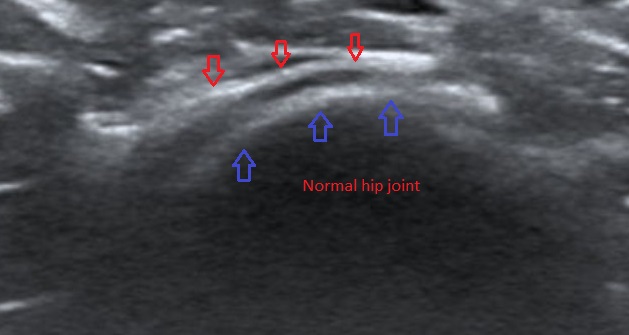

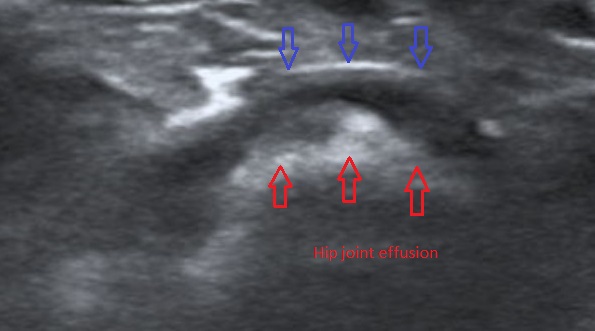

Part 1 of this blog introduced you to 12kg 7yo FS mixed breed patient who presented as a pretty typical iliopsoas tendinopathy – consistent pain on iliopsoas tendon palpation, a reluctance to move, and a clear iliopsoas core lesion evident on ultrasound. However, in the process of collecting our radiographic data, two things popped out at us. The first was that there was bilateral increased joint fluid evident in both stifles (Figures 1&2), yet there were no physical examination findings suggestive of cruciate disease or osteoarthritis. The second finding was that despite normal appearing hips on radiographs – with full recognition that the hip extended VD image is a poor screening test for hip dysplasia – on ultrasound, we found evidence of unilateral coxofemoral effusion (Figures 3&4).

Figure 1: Increased joint fluid is evident cranial to the distal femur (orange arrow), partially obscuring the meniscus, as well as caudally, compressing the fat line (blue arrow).

Figure 2: Normal lateral stifle radiograph. A normal amount of joint fluid can be seen, as demonstrated by a clear outline of the meniscus (between red arrows), and a lack of compression of the fat line caudal to the joint (blue arrow)

Figure 3&4: Ultrasound images of increased and normal joint fluid levels in the hip joint: the red arrows denote the femoral head, and the blue arrows denote the joint capsule. The hypoechoic (dark) region between is joint fluid.

When I hear a reported history of reluctance to move or “shutting down” on walks, back pain leaps to the top of my rule-out list. Second on that list is severe OA (which we don’t have in this case), and third on that list is immune mediated polyarthritis (IMPA). If this was an growing puppy, then panosteitis or hypertrophic osteodystrophy would be on the list as well.

Because of the concern re: IMPA, we called the owner and received permission to acquire joint fluid samples while the patient was still sedated. We collected samples from both stifles and both carpi, but elected to not collect a sample from the coxofemoral joints or tarsi because they are not as convenient to access as the stifles or carpi in a dog this size. The joint fluid was a normal colour, but subjectively had a decreased viscosity. Subsequent cytology confirmed neutrophilic inflammation in all 4 joints. This confirmed our suspicion of underlying IMPA, in addition to the iliopsoas tendinopathy.

IMPA can be both erosive and non-erosive, with the erosive form carrying a worse prognosis. Thankfully, non-erosive IMPA (IMNPA) is much more common. IMPA often presents with joint pain, swelling, and lameness, as well as more general symptoms. Lameness symptoms may wax and wane, shift between locations, or remain continuous. More chronic or severe cases can also demonstrate ligament laxity of affected joints, particularly the carpus or tarsus. General symptoms include lethargy, depression, anorexia, lymphadenopathy, polydipsia, and fever.

IMPA tends to affect the distal joints more frequently, particularly the carpi, tarsi, and interphalangeal joints. Conversely, septic arthritis tends to affect the more proximal joints. Cervical and tail region pain can also be a sign of IMPA.

IMPA is thought to be secondary to a type III hypersensitivity causing synovitis due to the deposition of antigen-antibody complexes. These complexes can be secondary to an infectious disease, including viral, bacterial, fungal, protozoal or parasitic infections. Implicated infectious agents include Mycoplasma, Borrelia, Leishmania, and Bartonella spp.. Diseases such as cystitis, pancreatitis, pneumonia, pyometra, endocarditis, discospondylitis, and heartworm have been implicated as well. It is estimated that 13-25% of IMPA cases relate to such conditions. An additional 4% appear to be secondary to enteropathogenic causes, and 2% are secondary to extra-articular neoplasia. The remaining cases (50-65%) are idiopathic in origin. Of course, these numbers can vary by region. I’m fortunate enough to live in Western Canada (Figure 5), where the incidence of tick borne disease and heartworm is essentially non-existent, and therefore a greater percentage of cases are idiopathic in origin.

Figure 5: Gratuitous picture of where my dogs get to play at the end of the work day because living in Western Canada is awesome.

Certain breeds appear predisposed to IMPA, with large breed dogs affected more frequently than small breeds. Dogs most frequently present at 5 years of age, with both sexes represented equally.

Certain drugs, usually antibiotics, have also been identified as triggers for IMPA. Vaccines have also induced IMPA, with symptoms appearing within 30 days of administration, but such cases often spontaneously resolve within days without the need for immunosuppressive therapy.

Diagnosis is based on clinical signs, supported by evidence of inflammatory change on bloodwork or imaging, but best confirmed by cytologic analysis of joint fluid obtained by arthrocentesis. IMPA and septic arthritis can have a similar cytologic appearance, but septic arthritis generally affects a single joint whereas IMPA affects multiple joints. For this reason, sampling should be from 3 or more joints. Culturing joint fluid is ideal, but false negative cultures are common.

Once a diagnosis is made, additional testing is required to rule out underlying causes such as tick borne disease, heartworm, fungal infection etc. If no underlying cause is found, a diagnosis of idiopathic IMPA is made by exclusion.

Treatment is either focused on the underlying cause if one has been found, or immunosuppressive therapy for idiopathic IMPA. Corticosteroids are frequently used as the first line medication. Most patients respond, and most can eventually taper off the medication over time, although 1 in 5 dogs may need lifelong therapy, and 15% do not respond. Supportive therapy is similar to that of any arthritic dog, albeit with a better long-term prognosis if they respond to medication.

In this case, there was an immediate response to prednisone therapy, with repeat cytology showing normal viscosity (cytology results are pending at the time of this writing). We anticipate decreasing the dose of prednisone 25% every 2 weeks while monitoring for relapse. Fingers crossed.