Laurie's Blogs.

Oct 2023

Canine Flexion Test for Orthopedic Joint Pain

I found an article that I wanted to dive into deeper. So, this week’s blog post takes you along that journey with me.

Here’s the article:

Front Vet Sci. 2022 Dec 15;9:1064795.

History

The flexion test comes from equine veterinary practice as a physical examination technique developed to determine joint health and locomotion evaluation. The flexion test (FT) is routinely performed during gait assessment, lameness evaluation and pre-purchase examinations.

During the flexion test, a suspected joint is held in a flexed position (which compresses the joint and stretches it’s surrounding soft tissue structures) which can elicit pain If there is any of these components. The flexion test is held typically for 1 minute, following which the horse is immediately walked or trotted on lead on a hard surface. An increase in lameness indicates that the flexed joint tested was/is responsible for the lameness.

Methods

The canine flexion test has routinely been used for 20 years in the referral orthopedic department of Ghent University in Belgium as part of the veterinary orthopedic examination.

As such, this study is retrospective, and reports on the clinical records from all orthopedic

patients presented for lameness complaints (not lame, to severe upon presentation) between 2009 and 2020.

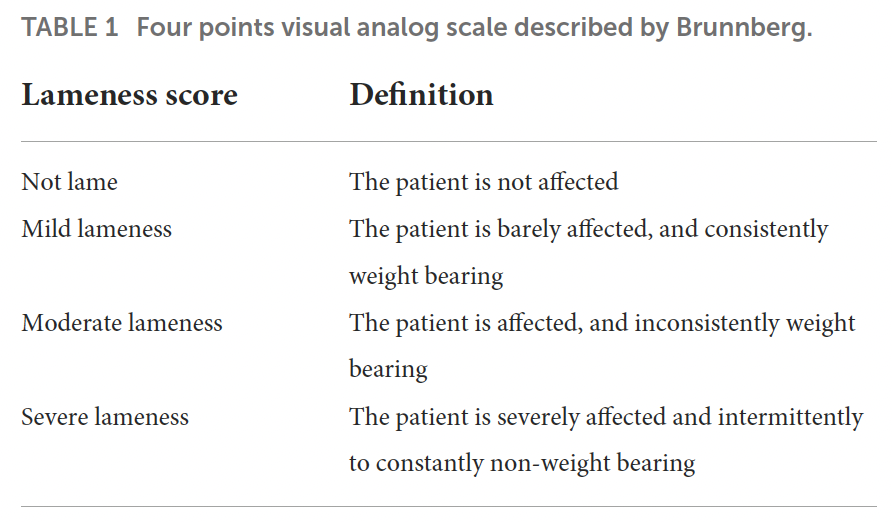

Each patient was assessed by one of the diplomates in veterinary sports medicine (ECVSMR). As part of the assessment, the dogs received a lameness score prior to and then after a one-minute flexion test.

Results

When all criterion was factored in, 1,161 patients / records met the study inclusion parameters.

“According to the selection criteria, the studied population gathered 612 males (52.7%) and 549 females (47.3%). Among those, 395 patients were neutered (34%), and 766 were intact (66%). The age of the patients ranged from 0.1 year (1.2 months) to 16.7 years (median 3.8 years; Figure 1). The dogs were classified into weight categories for statistical analysis purposes: 106 small dogs (under 10 kg; 9.1%), 272 medium dogs (10–25 kg; 23.4%), 619 large dogs (25–45 kg; 53.3%) and 164 giant dogs (over 45 kg; 14.1%). One-hundred and forty breeds were represented among those categories.

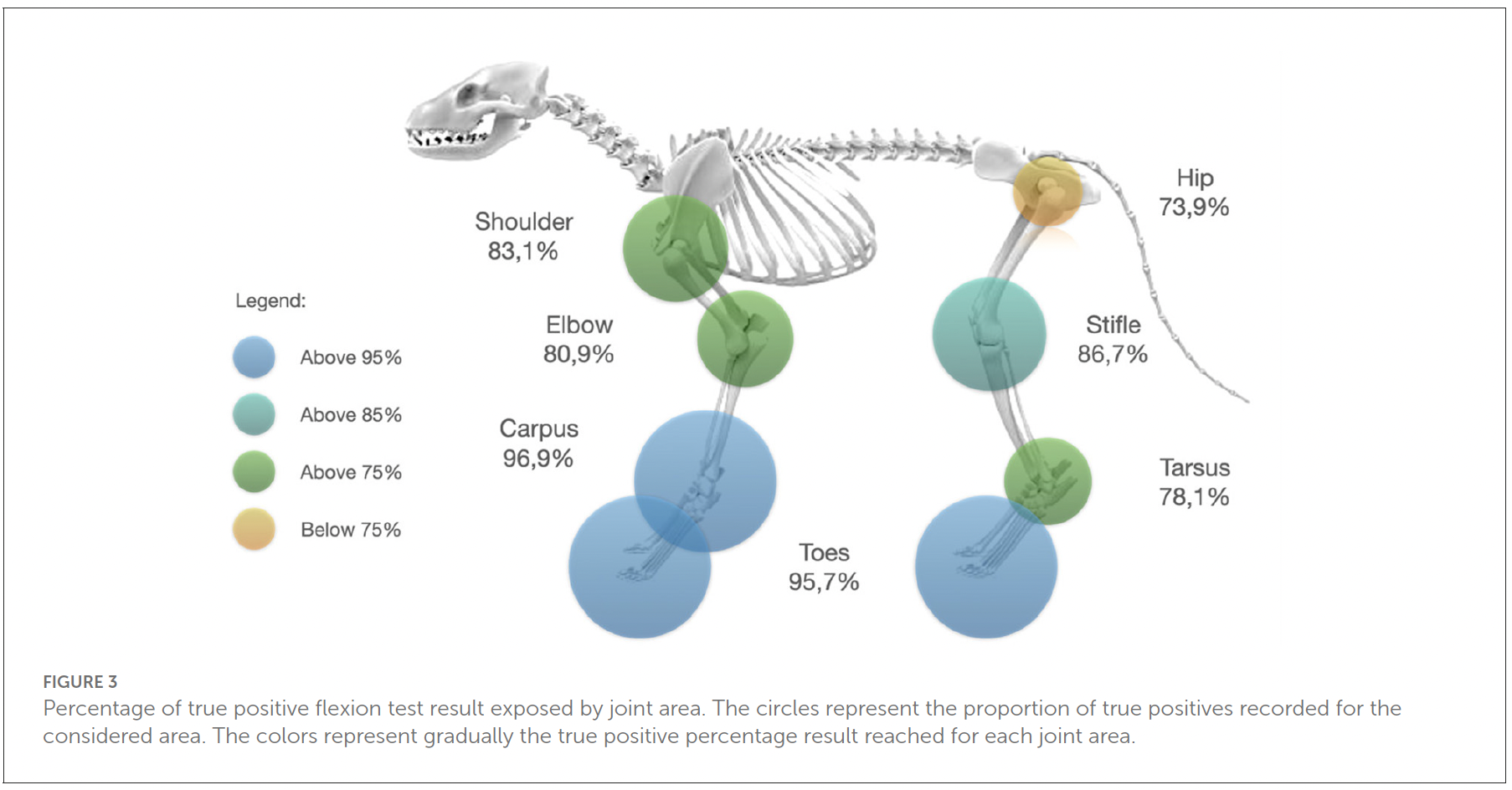

From the 1,161 patient’s files fitting the selection criteria, 867 dogs had a front limb FT (74.7%) and 294 underwent a hind limb FT (25.3%). The tested joints were the shoulder (101 tests, 8.7%), the elbow (693 tests, 59.7%), the carpus (32 tests, 2.8%), the hip (69 tests, 5.9%), the stifle (165 tests, 14.2%), the tarsus (32 tests, 2.8%) and the digits (69 tests, 5.9%). Among those 40 tests were performed on the digits of the front limb (57.9%) and 29 tests were performed on the digits of the hind limb (42.1%).

The patients were spread into four categories of lameness scores: not lame (238 patients, 20.5%), mild lameness (458 patients, 39.5%), moderate lameness (375 patients, 32.3%), severe lameness (89 patients, 7.7%).

The FT showed 82.8% (95%IC: 80.5–84.9) of true positive results (961 cases) against 17.2% of false negatives (200 cases). Given the study design that exclusively selected for cases with confirmed pathology in the joint that received the FT, no false positives (positive flexion test in the absence of a confirmed associated pathology) nor true negatives (negative flexion test on a normal joint) were identified.”

Regarding the lameness score, most of the false negative results to the FT were obtained when dogs were initially not lame or when they presented a severe lameness score.

Discussion

Here, I want to discuss MY thoughts – Not those from the paper! I have a few issues with this paper, but I’ll start with the positives. I like that this study is evaluating a technique that is typically used and relied upon in a different species. (Heck, that’s what I do day in and day out with my human knowledge.) I think that the addition of this test to a physical examination protocol might benefit an inexperienced veterinarian as he/she is developing their physical exam skills.

However, I find fault in this test for reasons that the actual discussion from the paper didn’t even mention.

1) What is missing from using the flexion test on a dog as compared to a horse is the use of nerve blocks to confirm that the joint being assessed is the one causing the lameness.

2) As such, the flexion test in a dog could very well pick up an ‘adjunctive’ site of pain that isn’t the true source of the lameness. Much like relying on an x-ray that may very well show arthritis in a joint, but the arthritic joint isn’t the source of the pain or lameness.

3) The test does not contribute to a gain of information that a detailed physical exam would produce. For example, if a dog is reproducibly painful with carpal flexion, I will further evaluate the carpus. Do I need to do a flexion test and ask the dog to walk and see if lameness will be made worse? I don’t think so.

4) This test has the potential to steer an examiner into thinking that all lameness stem from peripheral joints. Where does this leave lameness issues that stem from the neck, ribs, lumbar spine, or sacroiliac joints?

Conclusion

Again, MY conclusion, not that of the paper. I will not be adding this to my repertoire of examination techniques. That being said, I am grateful to the authors for giving me the chance to evaluate my thinking when it comes to this evaluation technique!